Stories below:

1. Mastodon Bones

2. Bellevue Lime Kiln

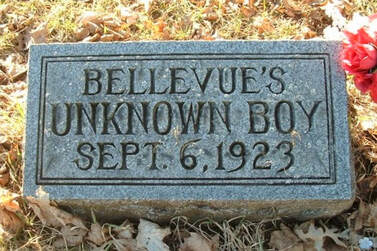

3. Bellevue's Unknown Boy

1. Mastodon Bones

2. Bellevue Lime Kiln

3. Bellevue's Unknown Boy

Mastodon Bones at Bellevue Historical Museum

by Deb Malewski

As printed in the County Journal

In 2014, Dan LaPointe, the owner/operator of Precise Construction in Bellevue, was digging a small fishpond for his neighbor, Eric Witzke, between Bellevue and Olivet. It was intended to be about 200 square feet in size. By the time the excavation was done, however, the site had grown considerably larger, and the remains of a prehistoric mastodon were in their hands.

An expert from the University of Michigan Museum of Paleontology was called in. He identified the remains as a five-ton male mastodon that lived more than 10,000 years ago. 42 bones were found, including ribs, legs, massive shoulder and hip bones, the base of a tusk, and numerous pieces of vertebrae. The animal would originally have had about 280 bones. Tool marks on some of the bones indicate that the animal might have been butchered by humans.

According to Wikipedia, “Mastodons disappeared from North America as part of mass extinction of most of the Pleistocene megafauna, widely believed to have been caused by a combination of climate changes at the end of the Pleistocene combined with overexploitation by Clovis hunters.”

This is not the first evidence of the mastodon in Michigan. There are 350 sites where mastodon remains have been found in the state, but only four in Eaton County. None have been found north of the Mason-Quimby line, which stretches horizontally across northern lower Michigan.

The mastodon is easily identified from the woolly mammoth. Mastodons were shorter and stockier than mammoths and had shorter and straighter tusks. Mastodons were wood browsers and their molars have pointed cones adapted for that type of diet, as opposed to the flat teeth intended for grinding that the mammoths used for grazing.

The initial plans were to display the ice-age creature locally for a while, and eventually donate them to the University of Michigan museum.

“The university would just put them in storage,” Mary Critchlow, secretary of the Bellevue Historical Society, lamented. “But they are something for a little town to brag about.” Supporters felt that the bones should remain in Bellevue.

“It’s special, something you don’t see in every museum,” added Critchlow.

Fundraising was done to help with the costs associated with the bones in the hopes of providing a special museum for them. The Bellevue DDA, partnering with the Bellevue Historical Society, held fundraising Mastodon dinners, auctions, and raffles at Stockhausen’s Old Bellevue Gothic Mill, highlighting a future location of a Mastodon attraction. A “Friends of the Mastodon” group was created.

For several years, the bones were displayed at Grandma’s Attic, an antique store. Currently, the bones are on display at the Bellevue Historical Society in their small museum beside the Bellevue library. They received the bones about a year ago, just about the time that COVOD-19 hit. “We had to close down right after as we got them,” Critchlow said.

They created a platform display for the artifacts in their museum, and the public can see them up close and even touch them. Surprisingly, the bones feel like bone or wood, feel light and porous, and have not petrified into stone.

“We’re a bit concerned about the future, though,” former Historical Society president John Dexter said. He is concerned for the future of the bones and the rest of their collection of Bellevue memorabilia. The active historical society members are aging and there haven’t been too many younger members stepping up to help maintain the growing collection.

The museum is open every Wednesday from 6 to 8 p.m. and can be visited anytime by appointment. It’s located at 212 Main Street, Bellevue, next door to the library. The museum can be accessed through the library.

Bellevue Lime Kiln

by Deb Malewski, as published in the County Journal

The bricks are askew in places, and weeds are growing up in other places, but the Dyer Kiln in Bellevue is one of Eaton County’s true historic treasures. This is where the early settlers to the county produced and distributed the lime that was needed to make cement to build their homes and businesses. Bellevue has a long heritage of lime production and had the first limestone kilns in Eaton County and probably the state. Limestone was discovered in the area in 1829 and became the chief product of the area and was the very first commercial industry in Eaton County.

Bellevue lime was considered superior to others as it was very high in calcium, which added to its strength. It was preferred by the native Americans, it was said, to make their pipes. Bellevue limestone ash was used in the construction of the Michigan state capitol.

Being the only supply of lime in the area, people would often have to travel 5 to 60 miles by horse and wagon to buy this needed ingredient for their fields, foundations, and plasterwork. They believed that the industry would continue forever and referred to the kilns as “perpetual” limestone kilns.

Only red-haired men worked at the lime kilns in Bellevue, it would seem. This anomaly was actually caused by the work conditions that the men experienced. The intense blasts of heat from the kiln were so intense, they say, that a pitman, or lime-burner, was marked with rusty red hair color. They worked in the intense heat ten to twelve hours a day and were paid about $1 a day. They usually wore a heavy wool undershirt, cheap overalls, ten-cent socks, and heavy shoes. Mittens made by their wives were the only protection they had for their hands from the heat. The men would emerge from a “draw” in the kiln drenched in sweat and would immediately take off their shirt to wring it out, no matter what the season, and hang it on the fence to dry, and dried their body with the shirt they brought to change into.

The job that required the greatest skill was that of the Limeburner, because only the most experienced would know when the limestone was properly burned and how much of it should be drawn out. Farmers would drive wagons of limestone up a ramp and dump the load. Fuel, usually wood, was fed for the fire through the doors at the bottom and the limestone was dumped in from the top. Workers would layer the stone between layers of hardwood, and then burn it. Limestone fertilizer would come out of the bottom of the kiln.

The kiln was originally built by Thomas Roberts in 1880 in partnership with Charles Dyer and was used until 1899. Dyer eventually bought out Roberts and operated the business alone.

There were other kilns in the area, with the oldest known kiln being on the north side of the Battle Creek river, across from the cemetery. The Holden kiln sat west of Bellevue near the railroad tracks. Lime from the Holden kiln was what was used in the state capitol, as it was so well-known for its great strength. The Meech kiln was located where the Portland Cement plant stood. It operated until the late 1890s when Michigan Alkali bought the property and tore down the kilns to set up their own business of shipping crushed rock for processing.

The kiln sat for many years as part of a neighboring farm until 1974 when the Eaton County Board of Commissioners bought it and then it became a community Bi-Centennial project. The group restoring it, spearheaded by Marilyn Frankenstein, received a grant from the Bi-Centennial Commission for $1500 to do the work. A small park was also included in the plan.

The Dyer Kiln and Park is located on the west edge of Bellevue, just south of M78 on Sand Road, and is the only surviving evidence of the once-thriving industry that flourished there. The half-acre park became a registered historic site for the state of Michigan in 1976. The ruins of the kiln are fenced off to help preserve it. The official seal of the village of Bellevue includes a drawing of the Dyer kiln in the logo.

by Deb Malewski, as published in the County Journal

The bricks are askew in places, and weeds are growing up in other places, but the Dyer Kiln in Bellevue is one of Eaton County’s true historic treasures. This is where the early settlers to the county produced and distributed the lime that was needed to make cement to build their homes and businesses. Bellevue has a long heritage of lime production and had the first limestone kilns in Eaton County and probably the state. Limestone was discovered in the area in 1829 and became the chief product of the area and was the very first commercial industry in Eaton County.

Bellevue lime was considered superior to others as it was very high in calcium, which added to its strength. It was preferred by the native Americans, it was said, to make their pipes. Bellevue limestone ash was used in the construction of the Michigan state capitol.

Being the only supply of lime in the area, people would often have to travel 5 to 60 miles by horse and wagon to buy this needed ingredient for their fields, foundations, and plasterwork. They believed that the industry would continue forever and referred to the kilns as “perpetual” limestone kilns.

Only red-haired men worked at the lime kilns in Bellevue, it would seem. This anomaly was actually caused by the work conditions that the men experienced. The intense blasts of heat from the kiln were so intense, they say, that a pitman, or lime-burner, was marked with rusty red hair color. They worked in the intense heat ten to twelve hours a day and were paid about $1 a day. They usually wore a heavy wool undershirt, cheap overalls, ten-cent socks, and heavy shoes. Mittens made by their wives were the only protection they had for their hands from the heat. The men would emerge from a “draw” in the kiln drenched in sweat and would immediately take off their shirt to wring it out, no matter what the season, and hang it on the fence to dry, and dried their body with the shirt they brought to change into.

The job that required the greatest skill was that of the Limeburner, because only the most experienced would know when the limestone was properly burned and how much of it should be drawn out. Farmers would drive wagons of limestone up a ramp and dump the load. Fuel, usually wood, was fed for the fire through the doors at the bottom and the limestone was dumped in from the top. Workers would layer the stone between layers of hardwood, and then burn it. Limestone fertilizer would come out of the bottom of the kiln.

The kiln was originally built by Thomas Roberts in 1880 in partnership with Charles Dyer and was used until 1899. Dyer eventually bought out Roberts and operated the business alone.

There were other kilns in the area, with the oldest known kiln being on the north side of the Battle Creek river, across from the cemetery. The Holden kiln sat west of Bellevue near the railroad tracks. Lime from the Holden kiln was what was used in the state capitol, as it was so well-known for its great strength. The Meech kiln was located where the Portland Cement plant stood. It operated until the late 1890s when Michigan Alkali bought the property and tore down the kilns to set up their own business of shipping crushed rock for processing.

The kiln sat for many years as part of a neighboring farm until 1974 when the Eaton County Board of Commissioners bought it and then it became a community Bi-Centennial project. The group restoring it, spearheaded by Marilyn Frankenstein, received a grant from the Bi-Centennial Commission for $1500 to do the work. A small park was also included in the plan.

The Dyer Kiln and Park is located on the west edge of Bellevue, just south of M78 on Sand Road, and is the only surviving evidence of the once-thriving industry that flourished there. The half-acre park became a registered historic site for the state of Michigan in 1976. The ruins of the kiln are fenced off to help preserve it. The official seal of the village of Bellevue includes a drawing of the Dyer kiln in the logo.